Sven Doering / DER SPIEGEL

Microsoft programmers hard at work in the Polish city of Wroclaw. Poland is currently experiencing massive economic growth. The third-richest man in Poland had arrived in Wroclaw by private jet in the morning. Leszek Czarnecki, a slim, tanned man, is now sitting on the 12th floor of the Wroclaw Arcade, gazing out at the center of the formerly German city. Czarnecki owns the arcade, an office building and shopping center complex.

He doesn't spend much time in this office, and the furniture looks like it could be from Ikea. It's the office of a man who doesn't feel a need to impress his guests. It has a view of the construction site of the "Sky Tower," which, when completed in the spring, will soar up 212 meters (695 feet), making it Poland's tallest building. Czarnecki also owns this new building.

He came to Wroclaw today to set up a new company, but by noon he'll already be back in the air on the way to his next destination. The 48-year-old Czarnecki, a restless man, has established a number of firms in recent years, including a high-end furniture company and a bank that specializes in the very rich. Getin Holding, which he owns, acquired a few small financial service providers and insurance companies and bought up all the shares in Allianz Bank Polska. About 2,000 jobs were created in the process. Czarnecki's various businesses are all doing splendidly. And the global economic crisis? It was non-existent for Czarnecki as it was, in fact, for all of Poland.

Europe's Most Optimistic People

The country has benefited from its accession to the European Union and globalization more than almost any other. Twenty years ago, the deeply Catholic country was largely agricultural and considered backward and provincial, a millstone around Europe's neck. Since then, however, Poland has experienced an almost nonstop boom.

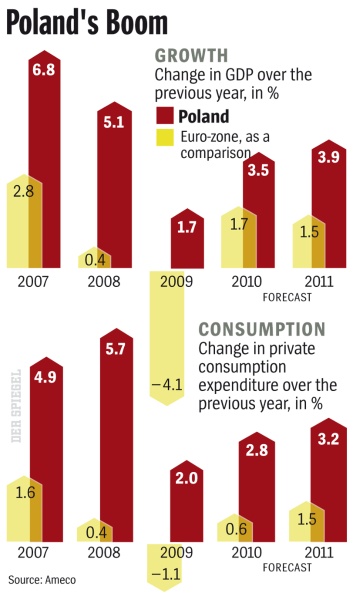

Even when the rest of Europe was suffering through a recession in 2009, Poland's economy grew by 1.7 percent. Thanks to its accession to the EU in 2004, unemployment fell from more than 20 percent to about 8 percent today.

The boom has been most evident in the cities. Warsaw and Poznan, for example, have full employment. According to surveys, Poles are among Europe's most optimistic people. They have never had it as good as they do today.

Warsaw is also at peace with itself politically. Prime Minister Donald Tusk runs the government with a stabile majority, while nationalist extremists on the left and right are no longer represented in Poland's parliament, the Sejm. Poland is now on excellent terms with Berlin and has toned down its rhetoric toward Moscow; the country is also no longer seen as an unpredictable obstructionist in Brussels. Almost a quarter century after the collapse of the Soviet bloc, the country of 38 million has become a respected regional power.

Dreaming Up New Business Ideas

Hardly anywhere else is the Polish economic wonder as much in evidence as it is in Wroclaw. When Leszek Czarnecki was defending his doctoral thesis at the city's business school in 1987, Poland was still paying homage to the socialist planned economy. Czarnecki, an extremely talented student and avid diver, formed a company for underwater welding with a few friends. "We were 10 times cheaper than the corresponding government company, and we were also better and faster," he says.

When the Iron Curtain fell, Czarnecki sold his shares. He leased a Mercedes with the proceeds, and in doing so realized how profitable the leasing business was. He promptly entered the leasing market for cars and construction machinery. He sold his company 11 years later to the French bank Crédit Agricole for €200 million ($270 million). Czarnecki had become a rich man.

Today he is worth more than €1 billion and his company Getin Holding owns subsidiaries in Belarus, Russia and Ukraine. Czarnecki is constantly dreaming up new business ideas. When asked where he gets his inspiration, he says: "Musicians can't explain why a new melody pops into their heads during their morning shower."

Foreign investment is less responsible for the Polish economic miracle than the ingenuity of the country's entrepreneurs. Their small- and mid-sized companies produce primarily for the Polish market, so that only 40 percent of the economy is dependent on exports. Consistently high domestic demand and the Poles' love of consumption prevented the country from sliding into recession during the 2009 crisis.

In Wroclaw, the Poles work primarily in Polish companies. Only 40,000 of the 150,000 new jobs created in the region in the last eight years were the result of foreign investment. And yet these are not low-wage jobs. The country is no longer a place for foreign companies to outsource their work. In fact, the West has discovered the value of Polish workers, men like Andrzej Rusewicz, for example.

A trained programmer, he left Wroclaw in 1981 when the communists cracked down on the Solidarity movement. Rusewicz moved to the United States and became a mathematics professor in Minneapolis. "I always dreamed of coming back," he says. Recently, that dream came true and he has been back in Wroclaw managing a team of programmers since last April.

Part 2: A More Open and Easygoing Country

It feels like a startup in the offices across from Czarnecki's new skyscraper, amid the cubicles, orange beanbag chairs and isotonic soft drinks in the refrigerator. Here, some 50 programmers are developing components for Microsoft's Bing search engine and other software. "There are some very good computer scientists here," says Rusewicz. The most talented professionals earn almost as much in Wroclaw today as they do in Boston, he adds. "The young people in Poland are highly motivated."

After returning from the United States, Rusewicz was astonished by the enormous shift in the mentality of younger Poles. The country's historic traumas -- the suffering under the Nazis, the Katyn massacre, during which Soviet intelligence agents wiped out almost the entire Polish elite, and the depressing period under the communists -- were no longer an issue. "None of the people working here are interested in the Polish cult of martyrdom, which preoccupied the country for decades," he says.

Poland has become more open and easygoing, which has also helped ease tensions with its neighbors, particularly in the West. Rafal Dutkiewicz, who has just won reelection as mayor of Wroclaw with more than 70 percent of the vote, senses this on his trips abroad, to Berlin, for example. The German capital is a three-hour drive from Wroclaw, while the trip to Warsaw takes four-and-a-half hours. He stays at the Grand Hyatt on Potsdamer Platz, he feels comfortable as he walks through the lobby in casual clothes, and his German is perfect. He meets with politicians and business leaders in Berlin, including German President Christian Wulff.

"We Poles Are Very Ambitious"

"The economy in Wroclaw is developing at a faster pace than in China," he says. Eight years ago, 200,000 passengers a year were arriving at the city's airport. Today it's two million. Since EU accession, wages have gone up by 50 percent in Wroclaw, and the city's tax revenues have tripled.

Dutkiewicz provides investors with the services of personal project managers, who are paid for with city funds and help them get whatever they need, from building land to construction permits to hotel rooms. "We Poles are no better than other nations, but we are very ambitious. We come from the very bottom and we want to get to the very top," he says.

It's been three years since the conservative nationalist Kaczynski brothers were in charge in Warsaw, but now the ice age in German-Polish relations has thawed. Following Prime Minister Donald Tusk's arrival into power in Warsaw, the dispute over the planned center for expellees in Berlin was settled without much fanfare. Today, Poles and Germans jointly advocate a more powerful EU military force.

Berlin and Warsaw have found even more common ground during the euro crisis. When Chancellor Angela Merkel was hesitant to agree to financial guarantees for Greece, she received surprising support from the Poles. Warsaw and Berlin are both committed to economic austerity. The Polish constitution includes a debt limit, and the banking sector is subject to strict controls that largely prevented Poles, unlike the Hungarians and those in some Baltic states, from borrowing in foreign currencies. In Budapest and Riga, such loans drove hundreds of thousands of small companies into bankruptcy during the crisis.

The National Bank of Poland, on the other hand, devalued the zloty and was thus able to enhance Poland's export capacity. Prime Minister Tusk, eager not to relinquish this instrument too soon, apparently doesn't want to introduce the euro until 2015. Nevertheless, Finance Minister Jacek Rostowski is already a frequent guest at meetings of the Euro Group.

The Merkel administration in Berlin hopes that Poland will become its ally in the conflict with the spendthrift southern countries in the Euro Group. This suits Warsaw's ambitions. In July, Poland will assume the chairmanship of the European Council for the first time, in the expectation that it will finally be able to cooperate on equal terms with Europe's big players.

"I am a fan of the European Union," says Wroclaw Mayor Dutkiewicz, who shares the sentiments of many Poles -- a people who could very well be the biggest champions of the European idea on the continent. "We have managed to derive maximum benefits from our membership," says Dutkiewicz.

Wroclaw's Most Impressive Export

This would probably never have happened without Poland's new view of the Germans. Anyone who disagrees should meet Marek Krajewski.

Krajewski lives on Grunwald Street, surrounded by a sedate middle-class world of high ceilings, textile wallpaper, thick carpets and massive tiled stoves in every room. Thick leather-bound volumes fill the antique bookshelf, while a modern flat screen TV is concealed to the left of the bureau.

As a child, Krajewski watched the Polish communists try to eradicate all things German in the city. They renamed the streets, flattened German cemeteries, removed old monuments and turned Breslau into Wroclaw. But not all traces could be erased. "The Poles were always secretly attracted to the German past," says Krajewski. "They feared the Germans because of history, and yet they admired them for their economic prowess."

He should know, because he now produces Wroclaw's most impressive export -- crime novels which have a German, Eberhard Mock, as the protagonist. Set in the period from the 1920s to the 1940s, Mock works for the vice squad in Breslau, as Wroclaw was once known. He is a hard drinker, corrupt and attracted to loose women. But he also hunts down murderers.

Mock's cases have been translated into 18 languages, and the German antihero is a superstar in Poland. Mock author Krajewski has already sold more than a million copies of his novels "Death in Breslau," "Ghosts in Breslau" and "Fortress Breslau."

"My success shows that the Poles are slowly overcoming their Germany complex," he says. The fact that they often spend their evenings with detective Mock is a sign of their new self-confidence, Krajewski believes. "We have become citizens of the world. We are no longer the victims."

Translated from the German by Christopher Sultan.

©spiegel.de

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.